In the hushed moments between what was and what will be, humanity has always found itself drawn to visions of endings. There’s something in our collective soul that recognizes patterns of collapse and renewal—from ancient tablets depicting cosmic floods to modern scientific graphs showing climate tipping points. We stand today at what feels like a threshold moment, watching pandemic waves, witnessing unprecedented ecological shifts, and sensing deep societal fractures.

The word “apocalypse” dances through our cultural conversations with new urgency, yet few understand its original meaning: not merely destruction, but revelation—an unveiling of truths previously hidden. What if our apocalyptic anxiety contains not just fear but invitation? What if prophecies across traditions aren’t merely predicting doom but offering wisdom for navigating transformation? This is the territory we’ll explore—where ancient visions meet modern evidence, where collapse narratives intersect with what we might call an ecology of hope.

Table of Contents

- 1 Key Takeaways

- 2 The Anatomy of Apocalypse: What We Mean When We Speak of Endings

- 3 Ancient Visions: Prophecies Across Traditions

- 4 Prophecy in Modern Times: Contemporary Apocalyptic Thought

- 5 Reading the Signs: Evidence of Systemic Stress

- 6 Beyond Doom: The Limits of Catastrophic Thinking

- 7 The Ecology of Hope: Finding Agency in Uncertain Times

- 8 Prophetic Imagination: Envisioning Regenerative Futures

- 9 Living at the End of the World: Spiritual Practices for Apocalyptic Times

- 10 Conclusion: Prophecy as Possibility, Not Prediction

- 11 FAQ

- 12 Sources

Key Takeaways

- “Apocalypse” originally meant revelation, not merely destruction, suggesting our current crises may unveil essential truths rather than simply end our story.

- Ancient prophecies across traditions share remarkably similar patterns of warning, transition, and renewal that can inform our response to modern challenges.

- Contemporary evidence of systemic stress is real but incomplete without recognizing our agency to respond creatively to collapse signals.

- Cultivating an ecology of hope requires specific spiritual practices that transform apocalyptic fear into prophetic action.

- The prophetic imagination offers a middle path between denial and despair, helping us participate consciously in cultural transformation.

The Anatomy of Apocalypse: What We Mean When We Speak of Endings

Before we can meaningfully discuss whether we’re living in apocalyptic times, we must recover the word’s deeper meaning. “Apocalypse” derives from the Greek “apokalupsis,” literally meaning “uncovering” or revelation. Far from the popular understanding of apocalypse as catastrophic end, the original sense indicates a disclosure of something hidden—a pulling back of the veil between apparent reality and deeper truth.

This distinction matters profoundly. When we confuse apocalypse (revelation) with eschatology (study of end times), we miss the transformative potential of apocalyptic thinking. Across spiritual traditions, apocalyptic literature follows a remarkably consistent pattern: it identifies a corrupt or unsustainable present condition, envisions a period of purification or transition (often through crisis), and culminates in renewal or transformation. This three-part movement serves as both warning and promise.

Psychologically, apocalyptic thinking emerges most powerfully during periods of social disintegration, political oppression, or ecological stress. It provides both explanatory power and meaning-making capacity during times when conventional narratives break down. To the marginalized or suffering, apocalyptic visions offer cosmic justice; to those witnessing system collapse, they provide an interpretive framework that extends beyond chaos into renewal.

What makes our current moment unique is the convergence of scientific evidence with apocalyptic intuition. We no longer need sacred texts to tell us that unsustainable systems eventually collapse; the spiritual truth and empirical facts are, in this rare moment, pointing toward similar conclusions. The question becomes not whether breakdown occurs, but how we might participate consciously in what follows.

Ancient Visions: Prophecies Across Traditions

The Judeo-Christian apocalyptic tradition provides perhaps the most familiar framework in Western consciousness. The Book of Revelation, written during a period of Roman persecution, offered early Christians a coded message of ultimate vindication. Its vivid imagery of beasts, plagues, and cosmic battles wasn’t meant as literal prediction but as resistance literature that sustained hope during oppression. Similarly, the Book of Daniel emerged during Babylonian exile, using apocalyptic imagery to assert that empire is temporary while divine justice is eternal.

Less familiar to Western audiences but equally profound are Indigenous prophecies that speak to our current ecological crisis. Hopi teachings about the emergence of the Blue Kachina describe a time when the natural world would fall out of balance, followed by purification and renewal. These prophecies have been misappropriated and commercialized, but their authentic core contains ecological wisdom rooted in centuries of careful observation.

The Maya calendar system, similarly distorted in 2012 end-time hysteria, actually presents a sophisticated understanding of vast time cycles. Rather than predicting doomsday, it marked the completion of one great cycle and the beginning of another—a cosmic transition point rather than an endpoint.

Eastern traditions offer cyclical rather than linear apocalyptic visions. Hindu teachings about the Kali Yuga describe an age of spiritual darkness that eventually gives way to renewal. Buddhist texts speak of the decline of Dharma—periods when spiritual teachings fade—followed by regeneration. What unites these diverse traditions is their recognition that decline and death are not the end of the story but necessary phases in larger cycles of becoming.

Comparative study reveals striking thematic consistencies across these traditions: the recognition that systems eventually reach limits, the role of human choice in determining the severity of transition, and the promise of renewal after breakdown. These ancient wisdom streams offer not escapism but resilience practices for navigating collapse consciously.

Prophecy in Modern Times: Contemporary Apocalyptic Thought

Secular Apocalypse: New Forms of End-Time Thinking

Our era has secularized apocalyptic thinking without diminishing its power. The Cold War’s nuclear threat introduced the first genuinely human-caused potential apocalypse—what philosopher Günther Anders called our “Promethean gap,” where our technological capacities exceed our ethical wisdom. Climate collapse represents the next evolutionary stage of this secular apocalyptic consciousness, with scientific consensus replacing prophetic authority as the source of warning.

The emerging discourse around artificial intelligence risks carries distinctly apocalyptic overtones, with concerns about an “intelligence explosion” creating existential outcomes beyond human control. These modern apocalyptic frameworks maintain the revelatory function of traditional prophecy—revealing the consequences of our collective choices—while grounding concerns in empirical evidence rather than divine disclosure.

Religious Responses to Modern Crisis

Religious communities have responded to contemporary challenges in divergent ways. Some fundamentalist movements interpret current events through dispensationalist frameworks that emphasize imminent divine judgment. The Left Behind series, which sold over 65 million copies, exemplifies how traditional apocalyptic imagery can be adapted to modern anxieties while curiously omitting ecological concerns central to our actual crisis.

In contrast, progressive religious voices increasingly frame the ecological crisis in prophetic terms. Pope Francis’s encyclical Laudato Si explicitly connects environmental degradation to spiritual and ethical failure. Indigenous religious leaders have emerged as powerful voices connecting traditional prophecies with contemporary activism, particularly around water protection and climate justice.

Cultural Expressions of Apocalypse

Our cultural imagination teems with apocalyptic scenarios. Dystopian fiction and film have exploded as a genre, from The Road to Don’t Look Up, processing collective anxiety through artistic expression. Post-apocalyptic settings have become so commonplace in entertainment that they risk normalizing collapse rather than mobilizing prevention.

Music across genres—from R.E.M.’s “It’s the End of the World as We Know It” to Anohni’s “4 Degrees”—processes apocalyptic themes with varying degrees of irony and earnestness. These cultural expressions serve a crucial psychological function, allowing us to rehearse emotional responses to breakdown scenarios and potentially develop greater resilience.

The psychology underlying modern apocalyptic thinking is complex. On one hand, apocalyptic frameworks can activate what psychologists call the “finite pool of worry” effect, where existential threats produce either denial or paralysis. On the other hand, properly framed apocalyptic narratives can motivate collective action by creating moral clarity and urgency. This tension between paralysis and mobilization defines our current cultural relationship with collapse narratives.

Reading the Signs: Evidence of Systemic Stress

The climate crisis represents the most comprehensively documented systemic stress signal in human history. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change has established scientific consensus that warming beyond 1.5°C threatens cascading systemic failures. We’ve already reached 1.1°C of warming, with current policies tracking toward approximately 2.7°C—a level that would render large portions of Earth uninhabitable for humans and countless other species.

Equally alarming but less discussed is the sixth mass extinction event currently underway. Species are disappearing at 100-1000 times the natural background rate, with approximately one million species at risk in coming decades. This biodiversity collapse threatens the ecological relationships that sustain human civilization, from pollination to soil formation to climate regulation.

The planetary boundaries framework, developed by the Stockholm Resilience Center, identifies nine critical Earth systems necessary for maintaining a stable biosphere. We have already exceeded safe operating limits for four boundaries: climate change, biodiversity loss, land-system change, and nitrogen/phosphorus flows. The remaining boundaries—ocean acidification, freshwater use, novel entities (like plastics and chemicals), atmospheric aerosol loading, and stratospheric ozone depletion—show various degrees of stress.

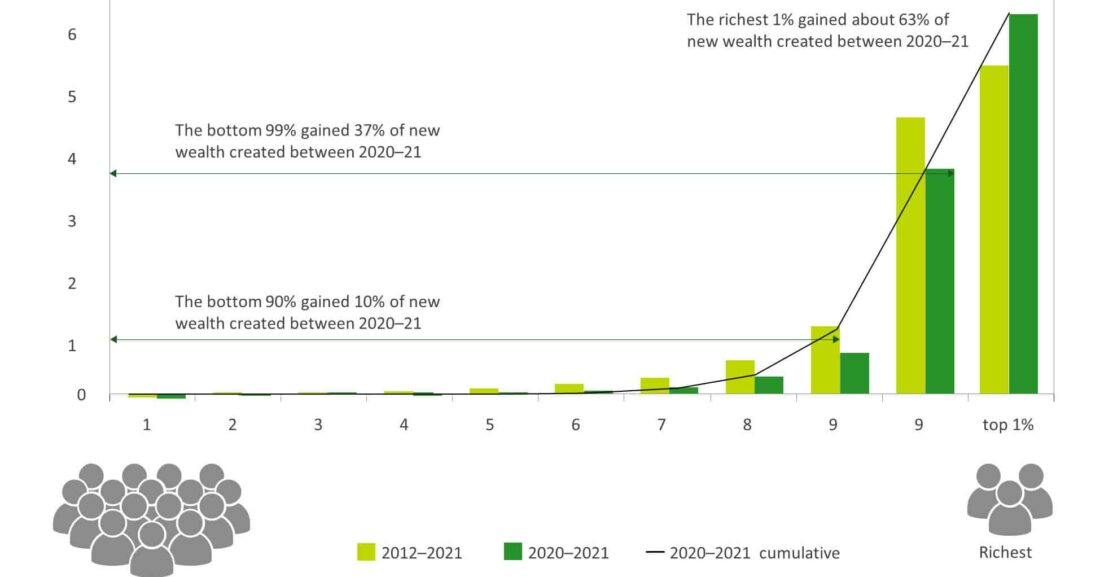

Social and political indicators amplify these ecological warnings. Rising inequality has reached levels not seen since the Gilded Age, with the richest 1% capturing nearly half of all new wealth created since 2020. Democratic backsliding affects countries representing 70% of global GDP, according to Freedom House. Information ecosystems increasingly fracture into isolated reality bubbles, undermining the shared factual basis necessary for collective problem-solving.

Technological developments add both risk and opportunity to this landscape. While artificial intelligence could help address complex challenges, it also introduces new vulnerabilities, including mass unemployment and unprecedented surveillance capacities. Biotechnology similarly offers both healing potential and biological threat multiplication.

These converging stressors create what systems theorists call a “perfect storm” scenario—multiple system failures reinforcing each other. The challenge becomes distinguishing between alarmism (which exaggerates threats) and legitimate alarm (which accurately identifies dangers requiring urgent response). The prophetic task involves holding the tension between truthful acknowledgment of crisis and the possibility of creative response.

Beyond Doom: The Limits of Catastrophic Thinking

While evidence of systemic stress is real, catastrophic thinking carries its own dangers. When fear becomes our primary lens, we experience what psychologists call “threat rigidity”—a narrowing of perception and possibility. Research in cognitive science shows that excessive fear activates our limbic system while deactivating the prefrontal cortex regions responsible for creative problem-solving and long-term planning—precisely the capacities most needed in crisis.

The history of failed apocalyptic predictions offers another caution. When specific end-time predictions fail to materialize—from William Miller’s 1844 “Great Disappointment” to more recent Y2K and 2012 scenarios—believers often double down rather than reassess their frameworks. Psychologist Leon Festinger’s concept of cognitive dissonance explains this pattern: when deeply held beliefs conflict with empirical reality, many people resolve the tension by deepening commitment to the belief rather than revising it.

This pattern reveals a shadow side of apocalyptic hope: the temptation toward escapism. Some apocalyptic thinking implicitly or explicitly encourages abdication of responsibility for the future, whether through belief in rapture, salvation through technology, or other forms of deus ex machina rescue. The most dangerous aspect of catastrophic thinking may be how it undermines agency—the sense that our choices matter in shaping outcomes.

Deterministic thinking itself proves inadequate when engaging complex systems. Climate scientist Tim Lenton emphasizes that tipping points work in both directions—degradation can accelerate past certain thresholds, but so can positive transformation. Social movements, technological adoption, and belief systems can all experience non-linear change when reaching critical mass.

The limitations of apocalyptic thinking don’t negate the reality of systemic stress but call for more nuanced engagement—one that acknowledges real dangers while remaining open to emergence and surprise. The prophetic task involves telling the truth about crisis without suggesting outcomes are predetermined or that human choice is irrelevant to what unfolds.

The Ecology of Hope: Finding Agency in Uncertain Times

Hope differs fundamentally from optimism. While optimism believes things will improve regardless of our actions, hope acknowledges uncertainty while committing to possibility. Environmental philosopher Joanna Macy distinguishes between passive hope (“hoping that”) and active hope (“hoping to”), with the latter focused on what we can contribute rather than what we expect to happen.

Macy’s “Work That Reconnects” offers a structured four-part spiral process for cultivating active hope: starting with gratitude, honoring our pain for the world, seeing with new/ancient eyes, and finally going forth with specific commitments. This framework transforms emotional responses to crisis into capacities for regenerative action.

Indigenous perspectives offer profound resources for hope amid uncertainty. The Anishinaabe concept of “seven generations” thinking—considering impacts seven generations forward and drawing wisdom from seven generations back—provides temporal depth often missing in contemporary crisis response. The Native American concept of “survivance” describes active presence rather than mere survival, emphasizing cultural continuity amid great challenge.

Spiritual traditions offer contemplative practices specifically designed for uncertainty. Buddhist teachings on impermanence (anicca) train perception to recognize constant change rather than fixity. Christian contemplative practices like the Examen cultivate attention to divine presence amid difficulty. Islamic concepts of tawakkul (trust in divine provision while taking action) balance surrender with responsibility.

Community rituals create shared containers for processing grief and recommitment. From traditional harvest festivals acknowledging both abundance and winter’s approach to newer traditions like the Dark Mountain Project’s “Uncivilization” gatherings, communal spaces allow expression of the full emotional spectrum crisis evokes—grief, fear, rage, and love—without isolation.

The ecology of hope recognizes that hope functions as a system rather than an individual emotional state. Like natural ecosystems, hope requires diversity (multiple strategies and perspectives), redundancy (overlapping efforts), and interconnection (alliance across difference). Building “hope ecosystems” means creating feedback loops where small successes generate energy for larger challenges, preventing burnout and isolation that often plague change efforts.

Prophetic Imagination: Envisioning Regenerative Futures

The biblical prophetic tradition wasn’t primarily about prediction but about speaking truth to power while offering alternative visions. Theologian Walter Brueggemann describes prophetic imagination as the capacity to both critique the dominant system and energize toward alternatives. This dual function—critical analysis paired with visionary possibility—holds particular relevance for our moment.

Contemporary prophetic voices emerge from unexpected corners. Indigenous land defenders at Standing Rock and beyond model both resistance to extraction and reverence for water as sacred. Youth climate activists like Greta Thunberg and Vanessa Nakate speak with moral clarity about intergenerational obligation. Regenerative farmers demonstrate practical alternatives to industrial agriculture while healing relationships between humans and land.

Different narrative frames shape how we understand and respond to system disruption. The “collapse” narrative suggests inevitability and promotes preparation or resignation. The “transformation” narrative emphasizes human agency and possibility. Most likely, reality includes elements of both—certain systems will collapse while others undergo rapid transformation, creating a mosaic future rather than a uniform scenario.

Art, story, and ritual play crucial roles in cultural transition periods by expanding imaginative capacity. Fiction like Octavia Butler’s Parable series and N.K. Jemisin’s Broken Earth trilogy explores collapse scenarios while emphasizing human dignity and relationship. Documentary films like The Biggest Little Farm demonstrate regenerative possibilities already underway. Public art installations like Ghost Forest bring climate impacts into visible urban space, converting abstract threat into tangible experience.

Practical frameworks help navigate discontinuity. The adaptive cycle in ecology describes how all living systems move through four phases: rapid growth, conservation (increasing rigidity), release (creative destruction), and reorganization. Our current global systems appear to be in late conservation phase moving toward release—understanding this pattern helps us anticipate and guide what emerges in reorganization.

Jem Bendell’s Deep Adaptation framework suggests four Rs for engagement with potential collapse: resilience (what do we most value that we want to keep?), relinquishment (what do we need to let go of?), restoration (what forgotten knowledge should we recover?), and reconciliation (with whom and what do we need to make peace?). This framework creates structured conversation spaces for engaging difficult futures without either denial or despair.

Living at the End of the World: Spiritual Practices for Apocalyptic Times

Cultivating equanimity—balanced awareness amid turbulence—becomes essential spiritual practice for apocalyptic times. Buddhist traditions offer specific techniques like noting practice (mentally labeling experiences as they arise without attachment) and RAIN practice (Recognize, Allow, Investigate, Nurture). These approaches develop the capacity to stay present with difficult emotions without being overwhelmed, maintaining responsive capacity rather than reactivity.

The shift from control to contribution represents another crucial spiritual movement. When outcomes remain fundamentally uncertain, meaning comes through alignment of action with deeper values rather than attachment to results. The Bhagavad Gita’s teaching on karma yoga—disciplined action without attachment to fruits—offers ancient wisdom suddenly relevant to climate activism and other forms of long-term systemic change work.

Grief work emerges as core spiritual practice for our time. When properly held, grief becomes not an obstacle to action but its foundation. Allowing ourselves to feel the pain of what is being lost—species, places, ways of life—honors their value while releasing energy previously used for denial or avoidance. Indigenous ceremonies like the Haudenosaunee Condolence Ritual demonstrate how communal grief practices can restore balance after great loss.

Community resilience represents spiritual discipline as much as practical strategy. Mutual aid networks—where neighbors directly support each other’s needs rather than relying on institutional systems—rediscover ancient patterns of reciprocity. Skill-sharing gatherings teach practical capacities from food preservation to conflict mediation. Time banking and other alternative economies practice new relationships between value and exchange. Each initiative builds both practical capacity and relational fabric necessary for navigating instability.

Perhaps most fundamentally, apocalyptic times call for practices of presence. When the future appears radically uncertain and the past insufficient as guide, our most reliable anchor becomes full presence with what is unfolding now. Contemplative traditions across cultures have developed sophisticated technologies for cultivating presence—from Christian centering prayer to Buddhist mindfulness to Indigenous ceremonial practices. These approaches don’t eliminate uncertainty but develop capacity to move through it with wisdom and grace.

Conclusion: Prophecy as Possibility, Not Prediction

As we return to the original meaning of apocalypse as “unveiling,” we might ask: What is being revealed in this historical moment? Perhaps our fundamental interconnection with Earth systems we long imagined we could control. Perhaps the failure of narratives of endless growth and separation. Perhaps our own untapped capacities for creativity and compassion amid crisis.

The invitation of apocalyptic consciousness isn’t to passive waiting for either destruction or divine rescue, but to active participation in the great turning of our time. Prophetic traditions remind us that periods of breakdown contain unique openings for structural change typically impossible during system stability. The task becomes neither clinging to what cannot last nor surrendering to cynicism, but midwifing what seeks to be born.

Consider: What do you love that you’re willing to fight for? What brings you alive that might also bring healing to your corner of the world? What skills or gifts might you develop that serve both immediate needs and longer transformation? These questions matter more than determining exactly how various collapse scenarios might unfold.

In uncertain times, wisdom often appears at the intersection of seeming opposites: holding both urgency and patience, both structural analysis and personal practice, both resistance to what harms and nurturing of alternatives. The prophetic stance combines unflinching clarity about what is breaking down with compassionate engagement with what wants to emerge.

Perhaps in the end, apocalypse isn’t something that happens to us but through us—not fate but invitation to participate consciously in a time of great unveiling. As theologian Catherine Keller suggests, apocalypse is not “the end of the world, but the end of a world.” Between worlds is precisely where prophets, artists, healers and visionaries have always done their most important work.

FAQ

What does “apocalypse” actually mean?

Contrary to popular understanding, “apocalypse” derives from the Greek word “apokalupsis,” meaning “uncovering” or “revelation”—not “destruction.” It refers to the unveiling of hidden truths rather than simply the end of the world, suggesting transformative potential within crisis.

How do different religious traditions view the end times?

Major traditions vary significantly: Christianity often emphasizes linear time culminating in final judgment; Hinduism sees cyclical time with recurring world-ages (yugas); Indigenous traditions typically emphasize renewal rather than termination; Buddhism teaches impermanence of all phenomena including world systems.

What spiritual practices help during times of crisis?

Beneficial practices include contemplative techniques for cultivating equanimity, communal rituals for processing grief, reciprocity practices that build resilience, gratitude practices that counter despair, and contribution-focused service that maintains meaning regardless of outcomes.

How can we maintain hope without denying reality?

Active hope differs from passive optimism by acknowledging difficulty while committing to possibility. It involves practicing gratitude, honoring pain rather than suppressing it, drawing on ancestral and ecological wisdom, and taking concrete steps aligned with deeper values regardless of guaranteed outcomes.